Rewinding a Nation

A technology that refused to stay quiet

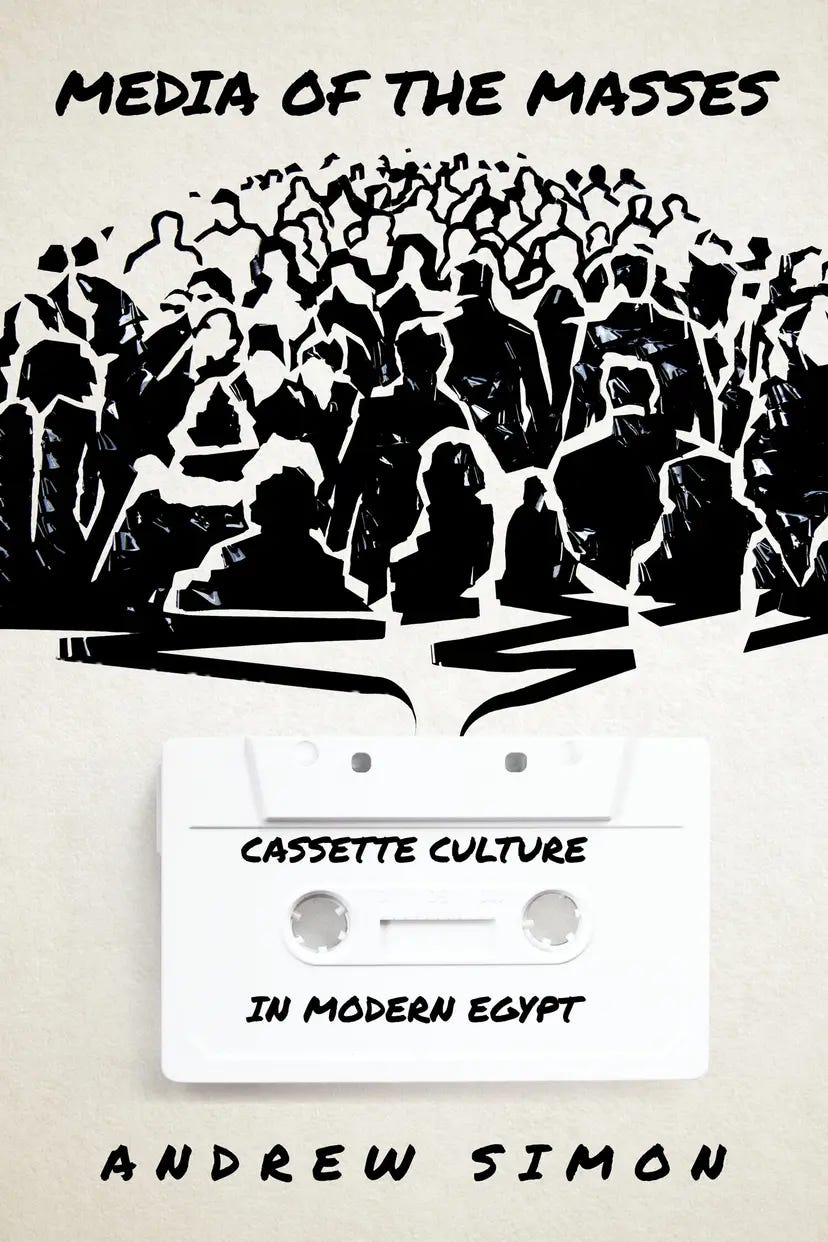

Andrew Simon’s Media of the Masses: Cassette Culture in Modern Egypt is the rare scholarly work that hums with life. It starts with dust-coated cassette tapes in a Maadi kiosk and ends with a sweeping rethinking of how Egypt’s modern history can be heard, felt, and remixed. The book insists that the stories of ordinary people are not peripheral to history; they are its pulse. And sometimes, those stories come recorded on cheap plastic tapes that once rattled in glove compartments, boomed from wedding speakers, or whispered sermon snippets into night-time living rooms.

Simon treats the audiocassette not as nostalgia bait, but as a device that helped millions bypass the gatekeepers of culture, morality, and politics. Before satellite television cracked the state’s monopoly, before the internet, before social media, there was the humble cassette. It democratized sound, irritated snobs, terrified censors, and entertained everyone else. Simon reconstructs that world with genuine affection, an archivist’s patience, and a comedic touch that turns academic prose into something closer to a very clever, very nerdy storytelling session.

Side A: When a Cassette Player Meant You Had Arrived

At the heart of the book is an argument that Egypt’s infitah years are better understood not through speeches and state communiqués, but through objects that circulated in people’s hands. One of the standout stories revolves around a now-famous photograph of three Egyptian workers in Iraq posing stiffly with a newly purchased cassette radio. The picture went viral decades later. In the moment it was taken, though, it was a declaration of arrival: the men had bought a prized device abroad for far less than what it cost back home, and they immortalized the purchase like someone today might do with a new iPhone held proudly at arm’s length.

Simon uses this image as a portal into a world of labor migration, aspiration, and shifting material desires. Under Sadat’s economic opening, Egyptians chased commodities that signaled their upward mobility. Cassette players became one such object. They were symbols of modernity, mimicry, independence, and sometimes pure bragging rights. This section of the book blends humor with sharp analysis: migrant workers hustling to bring back electronics, customs officials suspiciously sniffing luggage, black markets flourishing in the margins of legality. It’s a portrait of a society renegotiating its relationship with consumption, technology, and the very idea of “modern life.”

The cassette itself becomes a character. It slips across borders. It inspires theft. It triggers police reports so dramatic they read like miniature soap operas. It becomes the prized possession that people spend savings on, argue over, hide from tax officials, and proudly hold up in portrait studios. Simon’s attention to this material world gives the economic history of the 1970s and 1980s a warmth and texture rarely found in books about policy shifts and political speeches.

Side B: Egypt Sings, Shouts, Laughs, Copies, and Defies

In the second half of the book, Simon pivots from the cassette as object to the cassette as instrument. This is where the narrative takes off. Cassettes democratized who could produce culture. Anyone with a cheap recorder could now make music, sermons, comedy, or political commentary and distribute it without passing through the state’s cultural bottlenecks. Simon paints a vivid sonic landscape: wedding singers recording impromptu albums, preachers reaching audiences far beyond their mosques, Shaʿbi artists blasting through taxi windows, comedians circulating skits that never passed through a censor’s office.

One of the most compelling threads is the story of Sheikh Imam, the blind singer whose voice spread through informal recordings copied by ordinary Egyptians. His satire, dissent, and lyrical venom against the political establishment traveled hand to hand, tape to tape. Simon analyzes how Imam’s recording “Nixon Baba” punctured the triumphant story the state tried to project during the American president’s 1974 visit. This wasn’t just music. It was counter-history. It was Egypt talking back.

Simon shows how these tapes offered a parallel record of events—one that governments could not fully silence. Histories written by officials may have stayed neat and dignified; the ones recorded by cassette were messy, lively, mocking, contradictory, and often hilarious. In a country where official archives remain locked up or heavily sanitized, the cassette became a people’s archive, capturing a social world otherwise missing from the record.

The Great Taste Panic of the Cassette Age

One of the funniest and most revealing sections of the book is Simon’s dissection of elite anxieties about “vulgar” music. For decades, cultural authorities insisted that Shaʿbi songs, cassette sermons, and low-budget recordings were evidence of moral decay, bad taste, and the collapse of Egypt’s cultural heritage. What Simon uncovers, with both empathy and irony, is that these moral panics were rarely about art. They were about class. They were about who got to decide what counted as culture. They were about the loss of control.

Cassettes made taste democratic, which is precisely what frightened those who had long monopolized it. Suddenly, the cab driver, the factory worker, the housewife, and the student had as much say in what Egypt sounded like as the cultural mandarins of radio and television. The panic pieces published in state magazines read like unintentional comedy. Simon treats them with the seriousness they deserve, but never misses the opportunity to let their absurdity shine through.

Egypt’s Shadow Archives and the Historian as Treasure Hunter

Perhaps the most impressive dimension of the book is Simon’s methodology. He doesn’t rely on official archives—which are often closed, censored, or incomplete—but on what he calls “shadow archives”: flea markets, personal collections, photo studios, cassette shops, secondhand book stalls, and the dusty backrooms of electronics dealers. He pieces together fragments of Egypt’s acoustic life using interviews, marginalia, handwritten cassette labels, forgotten catalogues, magazine advertisements, crime reports, and photographs rescued from obscurity.

His chapters on these shadow archives read like mini-adventures. In one moment, he is sifting through piles of ephemera at Sur al-Ezbekiya; in another, he is interviewing a librarian who quietly preserved tapes no one else valued; in another, he is studying pirate recordings that traveled farther than any official broadcast. Through these encounters, he argues that modern Egyptian history requires a rethinking of what counts as an archive and whose voices deserve preservation.

The result is a fresh approach to Egyptian historiography; one that is sensory, democratic, and deeply human.

Listening to Egypt, Not Just Writing It

Simon’s great contribution is that he restores sound to its rightful place in modern Egyptian history. He insists that revolutions, economic openings, social anxieties, and everyday life were not just seen but heard. Egypt’s twentieth century, in his telling, is an acoustic story: the revving of cassette players, the hiss of rewound tape, the wail of Shaʿbi vocals, the booming sermons, the crackle of pirated recordings, the political chants rising from balconies and squares.

He encourages historians to break free from silent archives and imagine the past as a sensory world—alive, noisy, contradictory, and full of people who were constantly speaking, singing, arguing, and laughing their way through history.

A Tape Worth Replaying

Media of the Masses is one of those rare books that is both academically rigorous and genuinely fun. Simon writes with clarity, generosity, and humor. He respects his subjects without romanticizing them. He loves the messiness of Egyptian popular culture without turning it into spectacle. And he shows how a single technology can illuminate class tensions, state anxieties, economic shifts, creative subversion, and the stubborn ingenuity of ordinary people.

This is a book that deserves a wide audience. Not just Middle East specialists. Not just historians. Anyone interested in how culture works, how people improvise freedom under constraint, or how technology shapes everyday life will find joy in these pages. Like a good mix tape, the book is carefully curated, full of surprises, occasionally irreverent, and above all deeply personal.

Simon rewinds modern Egypt and plays it back with clarity and affection. And the sound is unforgettable.